Future Perfect*.

cancer's peculiar gift.

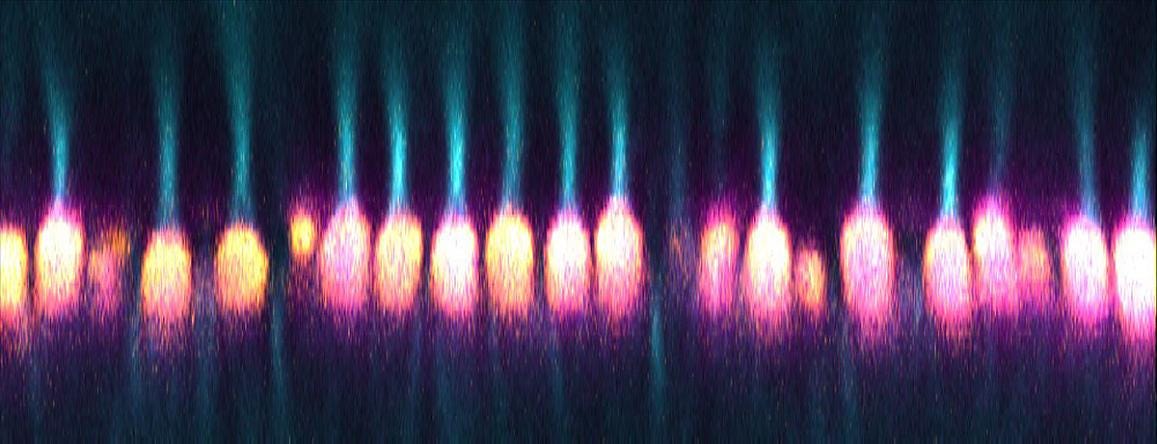

Image: Living cone mitochondria exposed to light. The path of light became concentrated with transmission from the inner to the outer segments of cone photoreceptors.

The future gets delivered to me in six-month chunks, the cadence of my cancer follow-ups. As an interval ends and the calendar becomes dotted with scans and appointments, the tension rises in me like any climax. So far, the results have been mostly bland, and I’m left with more waiting - until the next season of surveillance rolls around.

If I could become cancer-free, I would choose it, of course. It was such a gift to live unencumbered by the vexations of this human body. That future is up to science and, in some ways, fate, a word I use here to mean complexities too subtle and interwoven to tease apart. As such, it feels out of my hands completely, a particularly humbling feeling as a physician so used to “doing something”. Medical training does little to prepare us for this other side of the white coat.

It isn’t just bad news. These boluses of days and weeks in which I can live freed from treatment or surgery are sweeter than any that came before. The sense of beauty is so profound, even with its fears and anxieties, that a friend of mine living with cancer of her own agreed that if becoming free of it meant losing the perspective it gave her, she would rather keep it.

Can’t say I’m as brave as her, but I’m trying. When I was new to the patient position—and the see-saw of emotion it commanded—I called my meditation teacher Shinzen. He listened patiently and said, finally, in his Spock-like, algorithmic way, “While I’m prepared for the answer to be otherwise in your instance, to this point, for every one of my students with news like yours, cancer has been a positive experience.”

Positive? I could scarcely believe it, and on my most fretful days, I would deny this. On the other ones, though, when the snow is blowing in circles and a perfect flake lands in my lap, or I return from the bathroom to a table full of friends laughing, their faces creased with years of smiles, I know exactly what he means: this is the most beautiful future yet.

If I could describe the change in my view as a person and meditator, it would be as if someone turned up the colour, and everything is more vivid for it. The change in my experience is more subtle, harder to qualify. I can glean one thing: anger has no home in me anymore. It arrives at times—of course, I am human, riven with samskaras—but it never stays. In its place, more love than I thought possible. It is so precious, this one life that caught us like that dervish of snow, spinning us around our one true heart.

If the impenetrability of the future makes you anxious too, it’s not surprising. Hormonally, it is the exact same recipe as excitement, and biochemically, you could never tell the two apart. In the humming cylinder of a CT scanner, waiting for bad news, or about to accept the award for “artist of the year”— the same cascade. As we learn to sit with it, this profound unknowability, and understand the provocations of our overactive human mind, we come to see our nature and what we are capable of: anything. Not everything. Everything is what we’ll worry about, though, because it’s what we are.

This year, amidst all my particular medical tension and release, I reached a certain type of anniversary: I have been a doctor longer than not. Twenty-five years in emergency rooms with people on their worst day, reassuring them, helping them know that even though the future is unpredictable and unknowable, I can say something true about it: you will be cared for. That’s a future I can believe in.

In that, there is great cause for excitement. As I pondered this essay, I thought I would build a case about how profound our successes as human beings have been in my lifetime—for instance, halving poverty and hunger years faster than we thought possible, giving people with HIV long and healthy lives - and use that trend to make predictions about conflict and climate change, but I’ll make it another time. For now, I’ll simply remind us that who we are becoming, and the world we will build to reflect the love we have been shown, sits somewhere in the future too—beyond birthdays and death days. This month, guided by my homies at the CEC, we will practice holding tight with these feelings of anticipation so our next move toward the more perfect future will be even truer.

Happy new day. J.

Ps. If’n you want to connect IRL, and meditate about it, I’ll be holding down CEC on the last Monday. Put it in your calendars. If you want to get a head start, or an idea of what you’re in for, you can find some meditations here.

DATE: January 27 730 ET

TEACHER: James Maskalyk

THEME: Bring on the aliens.

James: One of my favourite answers to Fermi’s paradox is the reason we don’t hear from life elsewhere is because they have figured out they have the universe inside of them already, and have stopped looking for proof elsewhere. Along with the realization comes the insight that such a trajectory is inexorable for all life, is in fact its point, but can only be borne from self-inquiry, and no matter of explaining can facilitate it. As such, they have let their shifts and listening equipment rust, and are enjoying their one beautiful life that lasts forever. For this meditation, we are going to sit there, make antennas of ourselves, call that future forward.

*This essay originally published for the inimitable “Consciousness Explorers Club”

Very very interesting that anxiety and excitement are hormonally identical. As a lifelong anxietic, that provides much food for thought, and maybe even hope?

Equally interesting what you write: "who we are becoming, and the world we will build to reflect the love we have been shown, sits somewhere in the future too—beyond birthdays and death days."

The path forward so nicely expressed by these two thoughts--thank you.

I know but mostly forget the truth that we have the universe inside us already. Thank you as well for that reminder.

The razor edge of your life perhaps has given you, or at least brought to the forefront, the insight and grace you share.

Thanks again.

Yes. Humbling. Sorry to hear that you had to learn this thru cancer. For me in retrospect, the chronic disease diagnosis was a gift of perspective that I would not trade for my former “good health”.

“It was such a gift to live unencumbered by the vexations of this human body. That future is up to science and, in some ways, fate, a word I use here to mean complexities too subtle and interwoven to tease apart. As such, it feels out of my hands completely, a particularly humbling feeling as a physician so used to “doing something”.”